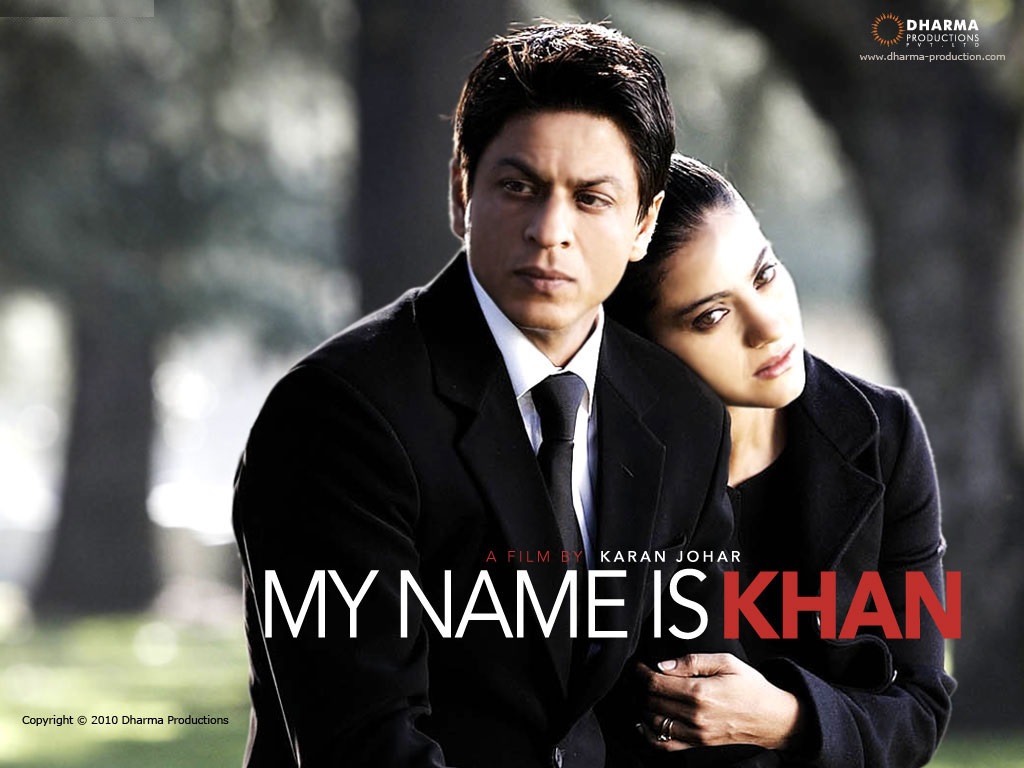

He is not a terrorist. Neither are millions of Muslims across the world. My Name is Khan returns to the question of confused Muslim identity in the wake of 9/11 with little novelty other than Shahrukh’s rediscovering himself as an actor playing a patient of Asperger’s Syndrome, a form of autism.

Rizwan Khan (Shahrukh) sees world in black and white, and the shades of grey do not quite register with him. To him what continues to be true from day one is that there are only two kinds of people – good and bad. His mother told him so with such fierce conviction that, to his mind, it stood true for all times. But then, the good lady had no idea that there were Twin Towers representing the economic supremacy of a certain nation, bringing down of which could spell disaster. She had no idea that in the circle of violence, the distinction between good and bad blurs beyond human recognition, and she did not live long enough to see the day the Towers came dashing down to the ground changing the world forever.

Those who attacked the WTC and were responsible for the deaths of so many were surely bad people and those who were out to punish these bad people were good. But the act of punishment or retaliation has violence in-built, and punishing for violence with violence is like trying to put off fire by fire. Hatred does not undo hatred, it adds to it. Somewhere down the line we conveniently ignored this simple principle. To contain the wrongdoers is one thing, to retaliate for the wrongdoing is quite another. The US did the latter, and the consequences have been sad so far.

Rizwan Khan is completely oblivious to the crooked ways of the world. After the death of his mother, he lands up in the pre-9/11 US and starts working with his brother selling cosmetics. He meets Mandira (Kajol), a separated single mother, who falls for Khan’s simplicity and inherent goodness. Her son, Sameer or Sam, gets along very well with Khan, too.

They marry and she becomes Mandira Khan, and her kid Sameer Khan. Happy life begins, and then arrives 9/11 bringing acute communal hatred in tow. Mandira’s business suffers because of the ‘Khan’ attached to her name. Things get worse when Sameer Khan is killed by some of his seniors at school. Mandira holds her marriage with Rizwan responsible for the death of her son, and asks him to leave, and Rizwan, in all his innocence, inquires as to when he was supposed to return. Mandira tells him to come back only when he manages to tell the President of the United States that his name is Khan and he is not a terrorist.

They marry and she becomes Mandira Khan, and her kid Sameer Khan. Happy life begins, and then arrives 9/11 bringing acute communal hatred in tow. Mandira’s business suffers because of the ‘Khan’ attached to her name. Things get worse when Sameer Khan is killed by some of his seniors at school. Mandira holds her marriage with Rizwan responsible for the death of her son, and asks him to leave, and Rizwan, in all his innocence, inquires as to when he was supposed to return. Mandira tells him to come back only when he manages to tell the President of the United States that his name is Khan and he is not a terrorist.

Rizwan sets out to accomplish the task, and the journey begins. A time comes when Rizwan is apprehended as a terror suspect while attempting to meet the President and is released only after there is a huge public outcry against the arrest and detention of someone who is not only undeniably innocent but is also a very kind human being.

At the heart of the movie is the everyday struggle of common Muslims in to come to turns with the altered reality in the post-WTC world. They, quite understandably, fail to see why they should be treated as terror suspects because of their religious identity alone. The problem further complicates because Islamist fundamentalism occupies the core of Islamist jihadmaking it natural for the authorities to be suspicious of the Muslims.

The flip side is that being treated as a terror suspect is insulting for an innocent Muslim just like any self-respecting, law-abiding person would hate being seen as a thief and would absolutely abhor the duration during which he was suspected of being a thief. Certainly, there are good people and bad people, and one’s religious beliefs have nothing to do with it. But when one is clubbed together with others and seen as part of a certain group by most, it is hard to not see oneself as part of the same group. Today, an American Muslim fails to understand if he is an American first or a Muslim or a human being. Killing the innocents is wrong, all religions say that including Islam. What about those who kill the innocents? Are they innocent? When your people are being killed, isn’t it part of one’s duty to defend tooth and nail? In the times of crisis, where should one’s loyalties lie?

Nation comes before the family. What if the nation attacks the family? Naturally, one would side with the family, and even if one does not endorse violent means, one cannot help feeling for one’s own people and getting angry with those responsible for their suffering. That’s the plight of the Muslims today. If the fundamentalist jihadis are ‘bad people’, the killers of innocent Iraqis and Afghans cannot really be ‘good people’ either. So, apparently, the choice is between two sets of ‘bad people’. And if that is the choice, one would naturally stand by one’s own ‘bad’ than by the other ‘bad’. Call him terror sympathizer or a terrorist or simply a Muslim, all he is doing is respond to the acts of violence the same way as any other human being would – with wide-eyed horror.

What My Name is Khan seeks to melodramatically convey is that it is high time we stuck to the time-honoured dictum of presuming innocence until proved guilty and not the other way round. The movie leans a little too much on drama with nothing great in the plot, but despite its shortcomings there is still no defect in what it stands for.

Originally written for and published in LAWYERS UPDATE [March 2010 Issue; Vol. XVI, Part 3]