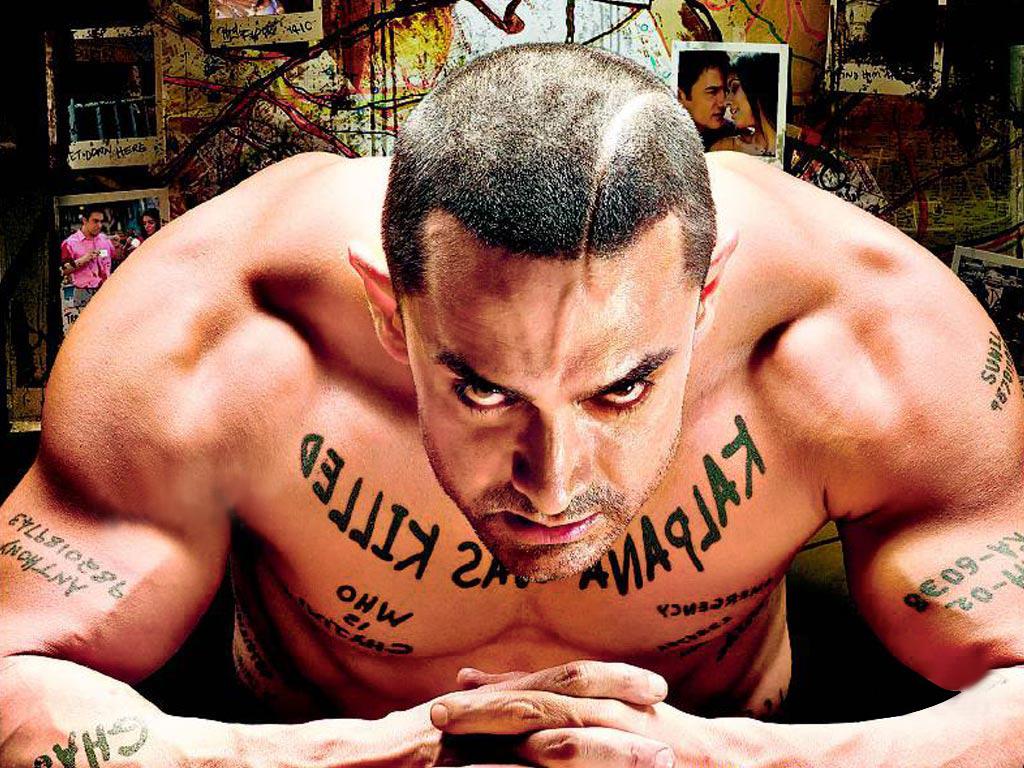

All he has is a terrifying moment frozen in time like a fossilized drop of blood as evidence of a heart-rendingly cruel crime committed in distant past. Every other moment that entered his life made a 15-minute stopover before a quick exit. The nightmare is all that he has to live by, and to annihilate the architects of his sordid past is what he lives for. And to assist his ever-failing memory he has what is carved on his soul tattooed on his body lest he should forget that Kalpana, the light of his life, was mercilessly killed by a monster called GHAJINI. This is Sanjay Singhania (the eight-pack-abbed, freshly body-built Aamir).

And he goes out to kill Ghajini and in the process kills many other. Naturally, with his 15-minute memory, he could easily forget why he killed right after killing. Then he would dig deep in his pockets and come up with a picture to match the face of the slain. He has already done a man in, and he doesn’t even know who he has killed or why. To know that he has to consult some photographic documents in his pocket.

Where does the law stand on this? A natural question, isn’t it? The mind of a criminal lawyer would start running different configurations of mens rea(guilty mind) and actus reus like a calculator works numbers. And the question can indeed be a complicated one to answer.

So, much so that if, for instance, Sanjay Singhania killed five people, it is possible that he is found guilty only for 2 or 3 murders despite having lost his memory at different stages during each of these murders. Sounds complex and baffling? No, it is not. It’s actually pretty simple. The law demands a clear presence of guilty mind when a criminal act is committed for the perpetrator of the crime to be convicted. And what is guilty mind? One should be aware of the nature and consequences of the criminal act, and that’s enough. The understanding of the relevant law or any law or even the existence of law, for that matter, is of no relevance.

In one situation Sanjay Singhania is on the very verge of killing the guy. The next move could dispatch the guy to heaven or hell (to be decided after dispatch). The guy lies right there – defenseless, motionless, horror-struck. And the memory slips. Mr. Singhania digs a picture out of his pocket to do a match. Now, the picture matches and Mr. Singhania proceeds with his ‘operation termination’. Verdict? Guilty, of course. And the reason is also very plain for anyone to see. At the time of murder the killer knows what he is doing.

Now, alter the situation a bit. Mr. Singhania is about to kill when his memory does the trick. He softens wondering what he is doing with a butcher’s knife in hand. His victim, in a last ditch effort to rescue himself, picks an iron rod lying nearby, and attacks Mr. Singhania. The only thing Mr. Singhania can now do is defend himself. And he does and in doing so ends up killing the person. In this case, at the time Mr. Singhania kills, he is simply acting in self-defence though he was the aggressor in the first place. In a normal situation, an aggressor cannot plead self-defence because no right to self-defence accrues against a preexisting right to self-defence. But in this case Mr. Singhania can, in all probability, successfully plead self-defence because his situation is much similar to that of a person who suddenly wakes up to an attack on his life and starts defending himself instinctively without thinking.

In another situation, Mr. Singhania throws a man off the building with the intention to kill, but somehow the man manages to hang on to a protruding iron rod, and Mr. Singhania’s memory fails him again. He finds himself standing atop a tall building with a man hanging on a thin iron rod. He instinctively extends a hand to pull the man up. The man gets to hold the hand but fails to take a good, life-saving grip, and descends to his death. It’s not all that complicated. The situation is the same as a person with the intention to kill lethally stabs a man and then regrets. He takes him to the hospital and does everything in his power to save his life, but fails. The man dies. That the assailant tried to save the life of the victim after delivering the death blow does nothing to dilute the intention to kill or the act of killing.

In another situation, Mr. Singhania throws a man off the building with the intention to kill, but somehow the man manages to hang on to a protruding iron rod, and Mr. Singhania’s memory fails him again. He finds himself standing atop a tall building with a man hanging on a thin iron rod. He instinctively extends a hand to pull the man up. The man gets to hold the hand but fails to take a good, life-saving grip, and descends to his death. It’s not all that complicated. The situation is the same as a person with the intention to kill lethally stabs a man and then regrets. He takes him to the hospital and does everything in his power to save his life, but fails. The man dies. That the assailant tried to save the life of the victim after delivering the death blow does nothing to dilute the intention to kill or the act of killing.

The court may consider the killer’s effort to save the life of his victim and may also take into account his remorse at the sentencing stage. However, the conviction is very certain. So, in this case Mr. Singhania’s ever-failing memory would not come to his rescue.

However, the most complicated legal question in case of Mr. Singhania would arise when the law considers that the man undergoing trial is someone who has no memory of what he has done and by virtue of his lost memory he may be legally unfit to stand trial. Only the same person who has committed the crime must be punished and no other. And a person is not body alone, which is why a person who goes insane after committing an offence is unfit for trial till the time his sanity is restored.

This case is slightly different than that of an insane person in that Mr. Singhania would readily understand the nature of killing someone and its legal consequences, but this is not the same Sanjay Singhania who killed. He is a new one, a clean slate. If he is told what he did, he may or may not feel remorse, but he is still in the position of a third person who considers the murders, the killer and the situation and then judges for himself if what the killer did was justified in his situation or not.

A person who has lost his memory cannot be convicted for the crimes he committed before the loss of memory because he is not the same person. Therefore, Sanjay Singhania, despite his sanity at the time of trial, would, in all probability, be found unfit to stand trial. And that position may remain unchanged for the rest of his life. However, he might still be considered too dangerous to be let out. Would it be just to incarcerate a man who is innocent in law? I would leave that question open.

Originally written for and published in LAWYERS UPDATE (April 2009 issue; Vol. XV, Part 4)