Child marriages have been part of a larger social reality in India as well as elsewhere for a long time, and while all child marriage might not have turned into disasters, certain social circumstances could and did turn some of them into blazing nightmares.

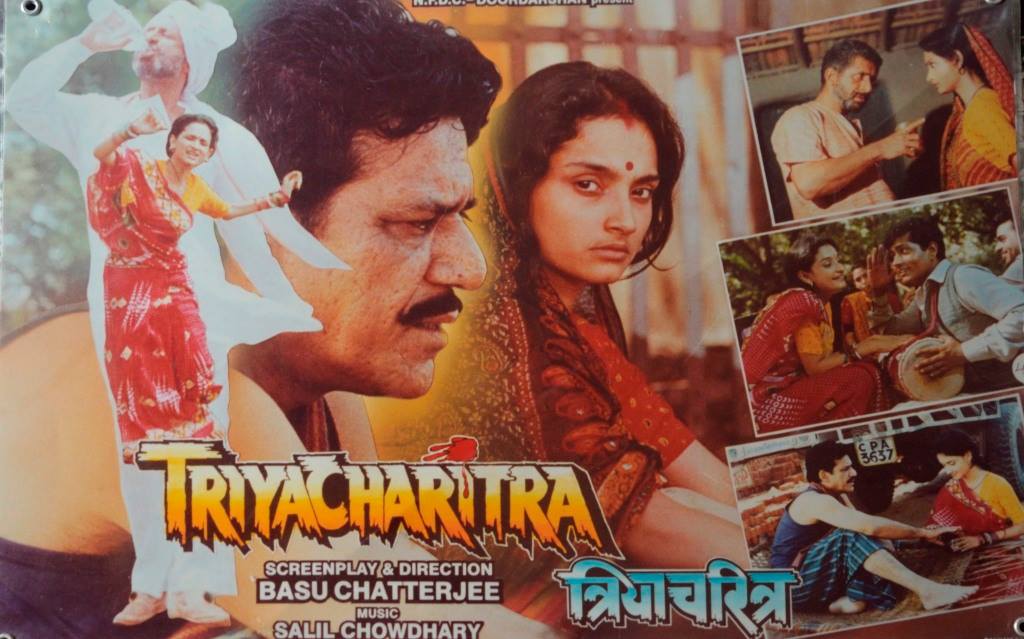

Triyachartira tells the story of a child bride, Bimli (Rajeshwari), who is betrothed to a boy at an early age of around 13, but, as per the customs, she would go to her husband’s house only when she comes of age, and when she does, the boy, is a young man who works as a daily wager in Calcutta, and does not send any money back home to his father, who is the only living parent he has. Bimli, on the other hand, supports her family by working at a brick kiln, where she has her fair share of admirers, including a truck driver who brings coal for the kiln, and wants to marry Bimli, like many others.

Bimli’s parents are not quite closed to the idea of remarrying Bimli, given the fact that Bimli’s husband has not returned for years and there is no news as to when he would get back. Bimli, however, is against a remarriage. Before Bimli’s parents could decide as to who to remarry Bimli to and before they could figure out how to get her to agree to it, Bimli’s father-in-law, Bisram (Naseeruddin Shah), comes calling and takes Bimli with her citing the stories he has been hearing about Bimli’s association with other men, which he finds objectionable and which, he says, are giving Bimli a bad name. Bimli’s parents have no option but to send Bimli with Bisram.

However, Bisram is in no hurry to call his son back and get his son’s married life started. Instead, being a lecherous man, Bisram intends to use Bimli as an object for the satisfaction of his own carnal desires. His attempts are dispelled, firmly in the beginning and then quite violently when Bisram keeps pressing on. But Bisram wants what he wants one way or the other. One night he drugs Bimli and rapes her. But before that he makes all the arrangements to make it look like Bimli had a night of passion with one of her alleged lovers and tried to kill Bisram by burning him alive. Bisram also manages to set things up to suggest that Bimli thought he was sleeping outside the hut and tried to kill him but failed only because he was at a temple for an overnight religious gathering. The plan works remarkably well because when Bimli regains consciousness, she acts exactly the way Bisram expected her to.

The panchayat is called to deliver a verdict. Bimli accuses Bisram of raping her whereas Bisram alleges that Bimli in conspiracy with one of her lovers tried to kill her, and managed to run away with his wife’s ornaments. What works against Bimli is that instead of raising alarm and calling the villagers, she chooses to go in search of her husband and is found in a train bound for Calcutta, wherefrom she is dragged to the village by the villagers to stand a panchayat trial. Although no ornaments are found on her, the possibility of her alleged lover having run away with them remains and is vociferously pressed by Bisram, who mentions the truck driver as a possible accomplice. Add the prejudices against Bimli from the stories about her, to the mix, and there is nothing going for Bimli apart from of a couple of shrieking female voices in her favour, which are summarily dismissed as biased and of no consequence.

The panchayat is called to deliver a verdict. Bimli accuses Bisram of raping her whereas Bisram alleges that Bimli in conspiracy with one of her lovers tried to kill her, and managed to run away with his wife’s ornaments. What works against Bimli is that instead of raising alarm and calling the villagers, she chooses to go in search of her husband and is found in a train bound for Calcutta, wherefrom she is dragged to the village by the villagers to stand a panchayat trial. Although no ornaments are found on her, the possibility of her alleged lover having run away with them remains and is vociferously pressed by Bisram, who mentions the truck driver as a possible accomplice. Add the prejudices against Bimli from the stories about her, to the mix, and there is nothing going for Bimli apart from of a couple of shrieking female voices in her favour, which are summarily dismissed as biased and of no consequence.

Triyacharitra, a Basu Chaterjee film released in 1994, is a commentary on the oppressive social circumstances of rural India, in which women like Bimli were handed raw deals. The film is based on Shivmurti’s novel ‘Tiriyacharittar’, and, being based on a work of literature, it exercises due narrative restraint without which the movie could have easily slipped into a woman-versus-society mode portraying the entire society as anti-women and could have indulged in wanton society-bashing. Triyacharitra keeps the story believable, and while it does not exonerate the panchayat from the wrong of delivering a flawed verdict influenced by certain male prejudices, it does not portray the panchayat as guilty of deliberately siding with Bisram.

It is a common but massive mistake to see Triyacharitra as portraying women as belonging to a vulnerable class pitched against the mighty oppressive patriarchal society with most men villainously opposed to or acutely insensitive to the idea of gender equality. The conclusion that the movie shows men in general as villains or patriarchal society as the culprit can be arrived at only if and when one conveniently chooses to ignore much of the movie. In telling Bimli’s story the movie does not really indulge in male bashing at all, and does not portray men siding with other men to oppress a woman so as to suppress the call for gender equality and kill feminine dissent. The movie accomplishes something much harder to achieve. It remains true to the reality and the story it tells without artificially tilting it to serve an agenda, and also does not try too hard to become any more relatable or comprehensible to the masses than it already is. The movies does explain the reasons why what happens to Bimli happens, and it’s not just patriarchal or male chauvinistic bias at work here.

Bimli is a playful young girl and does not particularly shy away from male company. The men around her, taking advantage of the closeness, try to pursue the own typical objectives with her, which she rejects every time without being offended by the attempts, for she somehow seems at home with such largely unobtrusive attempts at initiating courtship. However, most of her suitors believe that she has a thing for the truck driver (Om Puri), and attribute their rejection at Bimli’s hands to the romance between the two. They playfully tease Bimli about the romance, which she takes with a smile and without displaying a tinge of displeasure thereby allowing the impression to take root that there is indeed something brewing between the two. Even the viewers are led to believe that the two are romantically involved, for Bimli seems to not only enjoy but also approve of and encourage the flirtations that the driver frequently indulges in with her until she tells him rather sternly that he should not bring presents for her because she is not his wife. But this incident takes place in a hut and remains private while the stories of her being romantically involved with the truck driver keep in circulation, and, apparently, reach Bisram and perhaps makes him think of her as an easy woman. While it might be unreasonable to blame Bimli for the wrong impressions people carry of her, but those impressions are not completely baseless and do not come from cooked up stories.

Bimli is a playful young girl and does not particularly shy away from male company. The men around her, taking advantage of the closeness, try to pursue the own typical objectives with her, which she rejects every time without being offended by the attempts, for she somehow seems at home with such largely unobtrusive attempts at initiating courtship. However, most of her suitors believe that she has a thing for the truck driver (Om Puri), and attribute their rejection at Bimli’s hands to the romance between the two. They playfully tease Bimli about the romance, which she takes with a smile and without displaying a tinge of displeasure thereby allowing the impression to take root that there is indeed something brewing between the two. Even the viewers are led to believe that the two are romantically involved, for Bimli seems to not only enjoy but also approve of and encourage the flirtations that the driver frequently indulges in with her until she tells him rather sternly that he should not bring presents for her because she is not his wife. But this incident takes place in a hut and remains private while the stories of her being romantically involved with the truck driver keep in circulation, and, apparently, reach Bisram and perhaps makes him think of her as an easy woman. While it might be unreasonable to blame Bimli for the wrong impressions people carry of her, but those impressions are not completely baseless and do not come from cooked up stories.

An unrelated pair of a young man and a young woman might play Ludo behind bolted doors in all innocence, but the people outside the closed door cannot be faulted for drawing their own, more natural conclusions. Generalization, yes. Fallible, yes. Unreasonable? No. Something similar happens in Bimli’s. Her ease in associating with men works against her and she is taken to be ‘easy’. Her playful smiles and giggles at the mention of the truck driver does nothing to soften the ill repute. The same ill repute, concretized by the widely circulated stories about her male-friendliness and the truck driver tale in combination with the misstep of her trying to board the train and go off to Calcutta on the morning of the assault without raising an alarm about the rape, plays right into the hands of Bisram and gives almost unimpeachable credibility to Bisram’s story of Bimli’s culpability. And there lies the success of filmmaker Basu Chatterjee’s storytelling apart from the undeniable strength of the story and the script.

As viewers we have the omniscient viewpoint, by virtue of which we know what really happened, but from the perspective of the panchayat that decides the matter, Bisram’s version is a lot more credible than Bimli’s. While the movie depicts Bisram as a lecherous schemer, who does finally succeed in his evil designs, it exercises admirable restraint in not pushing the envelope further on to portray all men ganging up against a helpless woman in pursuance of some subtle, undeclared ‘patriarchal’ agenda. Bimli remains the victim of her unfortunate circumstances, and suffers the cruel punishment of having a scar burnt into her forehead with a red-hot iron rod by Bisram, the same man who raped her the night before and also proved to the world that she was nothing but a thieving trollop.

Originally published as part of my Movie Review column LEGAL SCANNER (Classics) in LAWYERS UPDATE [September 2015 Issue; Vol. XXI, Part 9].