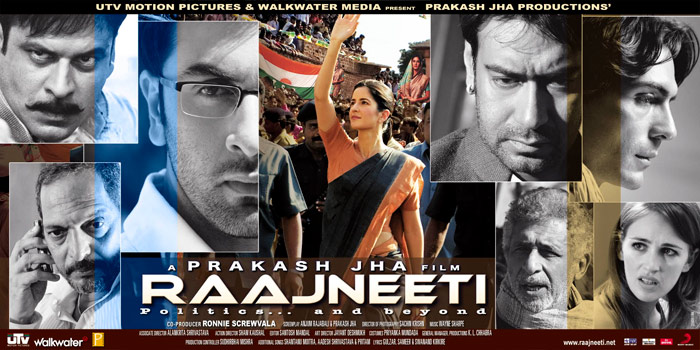

I wonder if Maharishi Ved Vyasa and Mario puzo whispered in each of Prakash Jha’s ears while he directed Raajneeti marrying the greatest epic poem of the East with the masterly pulp fiction of the West to dish out a Mahabharat-made-easy for the lovers of The Godfather.

Director Prakash Jha’s standing promise of telling the hard-hitting and discomfiting truth sans bollywood melodrama stands seriously compromised with little imagination and even lesser reality discernable in Raajneeti.

You have the same reluctant protagonist, who is all too upright to be tolerant of violent means and unholy ends, but finds himself right at the center of the things because his family is in deep trouble and desperately needs his help. He is unwilling but yields to the call of blood. Of course, the imprint of Michael Corleone on the character played by Ranbir Kapoor is unmistakable. He, much like his counterpart in The Godfather, takes to violence to match his adversaries in the war for survival. Like Michael, Ranbir, too has two women, one of whom comes from a foreign land and is killed by a car bomb. Likewise, the angry and impetuous Sonny Corleone is all too evident in Prithvi, Ranbir’s elder brother, played by Arjun Rampal.

The only difference being that in The Godfather it’s a crime family while in Raajneeti it’s a political clan. However, there is little difference in the way they operate.

And then there is Ajay Devgan playing Suraj, who has a distinct resemblance with Karna of The Mahabharata. Karna was the son of the Sun, and ‘Suraj’ is Hindi for the Sun. His father, played by Naseeruddin Shah, is Bhaskar, and ‘Bhaskar’ is, again, the Sun in Hindi and is synonymous with ‘Suraj’. The unwed mother casts her first son away, who later returns to be a formidable opponent to the rest of her sons, which is when she goes and meets him secretly and pleads with him to join his real brothers. Suraj turns down the request in much the same manner and on the same grounds as Karna does in the epic.

And then there is Ajay Devgan playing Suraj, who has a distinct resemblance with Karna of The Mahabharata. Karna was the son of the Sun, and ‘Suraj’ is Hindi for the Sun. His father, played by Naseeruddin Shah, is Bhaskar, and ‘Bhaskar’ is, again, the Sun in Hindi and is synonymous with ‘Suraj’. The unwed mother casts her first son away, who later returns to be a formidable opponent to the rest of her sons, which is when she goes and meets him secretly and pleads with him to join his real brothers. Suraj turns down the request in much the same manner and on the same grounds as Karna does in the epic.

Towards the end, when Ranbir hesitates in shooting Suraj, Nana Patekar reminds him the same way as Lord Krishna reminds Arjun that the war had not been fair, and since the unfair means were first resorted to by the enemy, it was morally open for him to use the same to gain victory. Arjuna releases the arrow there and Ranbir pulls the trigger here.

And here comes the moral dilemma pertaining to the use of questionable means in an unjust war fought on the uneven turf of politics against the unscrupulous enemies armed with limitless political power and influence rooted in unabashed political opportunism.

Although the moral debate has been there since time immemorial, the central question relates to the power-legitimacy equation. So, it is about whether power supplies the legitimacy or it is the other way round. When the parties involved in an all out political war are powerful enough to make, bend and break the laws, which of the principles, moral or legal or of any other kind, would still hold, if any and if at all? Naturally, the powerful would be in a better position to enforce the principles that serve their interest best, but such principles cannot completely ignore public interest to stand for long.

In The Mahabharata, the battle is fought to preserve and sustain the principles of righteous conduct, and Arjun is advised by Lord Krishna to see beyond the wrenching pain and suffering of having to kill his loved ones and fight for the right and the just. Thus, Lord Krishna counsels emotional detachment. The Mahabharata had to be fought because all ways of engineering peace had been closed and the Kauravas were bent upon defeating the rightful claim of the Pandavas. To forego the claim completely would have implied complicity in an act of injustice. The war was, therefore, inevitable in the interest of justice.

Jha seems to have missed the point completely and hit way off the mark. Violence in The Mahabharata is not selfish, vengeful or self-preservationist. It is meant to re-establish the foundational principles of righteous conduct.

In Raajneeti, however, it’s about wreaking vengeance and acquiring and retaining political power. Therefore, the resemblance with The Mahabharata is only at the superficial level of the story. The fundamental principles that the great Indian epic propounds find no place in Raajneeti, which is why it has no message to convey. Director Jha makes the politicians behave like gangsters, having generously borrowed from The Godfather, and ends up overlooking the crucial forces other than formal democratic institutions that work in a democracy to check such misuse of power.

In Raajneeti, however, it’s about wreaking vengeance and acquiring and retaining political power. Therefore, the resemblance with The Mahabharata is only at the superficial level of the story. The fundamental principles that the great Indian epic propounds find no place in Raajneeti, which is why it has no message to convey. Director Jha makes the politicians behave like gangsters, having generously borrowed from The Godfather, and ends up overlooking the crucial forces other than formal democratic institutions that work in a democracy to check such misuse of power.

Since Jha paints politicians in gangster colours without making necessary changes, he triggers a conceptual short circuit. Gangsters thrive on fear, politicians on public affection and sympathy. Gangsters would keep the public as far as possible, whereas the politicians would want the public to relate to them as closely as possible. Incidences of political violence inspire conspiracy theories, which, in turn, give rise to public discussions and political gossip. The effect of such sideline discussions are just too unpredictable and can be very profound in terms of public opinion. No politician would be willing to run the risk of turning the electorate against him in a democracy. For gangsters, of course, negative publicity is good publicity.

LTTE made the massive political mistake of plotting and carrying out the assassination of the former Indian Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi, and not only regretted it as a humungous political blunder, but also ended up paying a heavy price for it. Even the out and out terrorist organizations with political aspirations think very hard and long before resorting to assassination.

But the director, in a bid to enlarge the action on the screen, miniaturizes political reality of the day and turns the movie into a cartoon film of a projected political saga. It’s just a stale dish made with borrowed spices and served with bollywood garnish.

Originally written for and published in LAWYERS UPDATE [July 2010 Issue; Vol. XVI, Part 7]