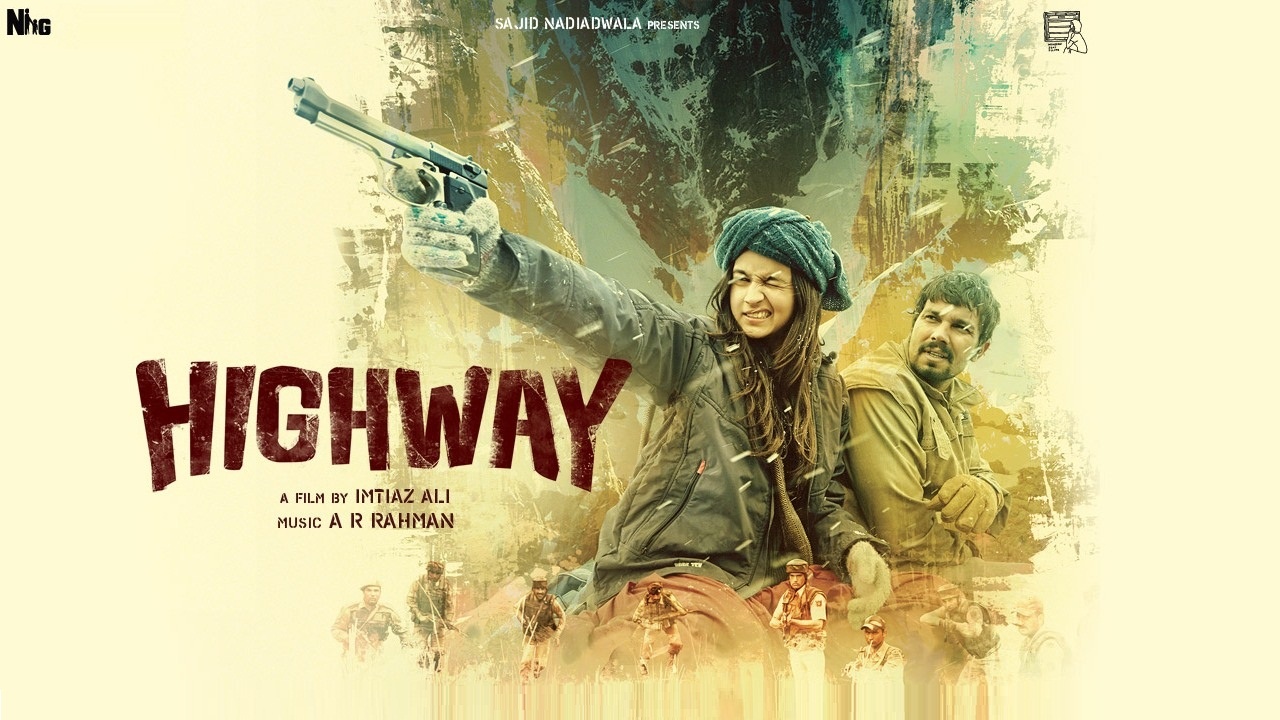

One can’t simply mix Stockholm Syndrome, Child Abuse and the idea of love-on-the-go in different proportions, throw in some rustic dialogues, and tout it as path-breaking cinema. It is a ‘different’ movie only to the most naïve of the audience; for the rest it’s a cocktail of The World Is Not Enough, Monsoon Wedding and Jab We Met.

Veera Tripathi (Alia Bhatt) wants to bask in the freshness of freedom, craves freedom from the shackles of expected political correctness and from the compulsion to be appropriate at all times. This purportedly free-spirited, rebel girl is the daughter of a wealthy man of considerable political influence. She is about to get married, and calls her husband-to-be over late at night, steals out of her house and asks him to take her for a long drive, which he refuses to do initially but concedes to ‘touching the highway’ and coming back after realizing that the girl wouldn’t back down. They stop for fuel. And despite being told not to, by a concerned would-be hubby, she steps out of the car to breathe in the air of freedom. Unfortunately, there is a robbery in progress and the robbers, on their way out, take the girl hostage and drive away in the couple’s BMW. The lead robber, Mahavir Bhati (Randeep Hooda), later realizes that the girl they had taken hostage is the daughter of a man of great means and political influence. They realize almost immediately that it was a shark on the other end of their fishing rod and there was no way they could drag it aboard their little canoe. They realize that holding the girl for ransom was not a viable scheme, given who the father of the girl was. But, Mahavir, in reckless disregard of conventional wisdom and the advice of his seniors in crime, decides to go ahead with the plan anyway.

To misdirect law enforcement agencies, Mahavir sends one of his associates to Bengal to make a few calls to the girl’s parents and later they also send a picture of the girl holding a recent Bengali language newspaper to indicate that she was alive and in Bengal. All this while Mahavir continues with the girl in a truck through Punjab and into Himachal Pradesh. After her first attempt to flee fails, she is no longer a hostile hostage but a willing companion, who even helps her kidnappers give the police a slip.

To misdirect law enforcement agencies, Mahavir sends one of his associates to Bengal to make a few calls to the girl’s parents and later they also send a picture of the girl holding a recent Bengali language newspaper to indicate that she was alive and in Bengal. All this while Mahavir continues with the girl in a truck through Punjab and into Himachal Pradesh. After her first attempt to flee fails, she is no longer a hostile hostage but a willing companion, who even helps her kidnappers give the police a slip.

Mahavir is a coarse man and does not treat his hostage with any genuine gentleness though he is not particularly cruel, overbearing or rough to her either. And he does save her from falling prey to the lust of a lecherous associate of his, who is hit and reprimanded by Mahavir for his act, which results in his leaving Mahavir and later helping the law enforcement agencies in locating Mahavir. With generous assistance from the Director the hostage is made to realize that the kidnapper is not much of an enemy. Consequently and predictably, she opens up and reveals her painful past replete with repeated sexual abuse as a child at the hands of her uncle condoned by her own mother. The kidnapper warms up to her, and his protective instincts come into play like they have been waiting patiently for decades to gush out at the right moment. Equation changes fast enough. And she is no longer a ‘deal’; she is a delicate flower in need of protection. And the flower self-confessedly likes the road more than any garden in the world, which gives the Director the opportunity to once again take us to the dry and twisty as well as the snow-lined roads of Jab We Met . He could have easily used some footage from Jab We Met itself and saved some shoot expenses.

The coarse, uncouth villain has a good side. In fact, he has no bad side at all. He is the victim of his circumstances, like the rest of us. The heroine, having grown up in a heavily protected environment, gets out to see the big, bad world, where nobody really cares. She finds the goodness in the bad, and falls in love with it. The bad she finds is a lot better than the best in her well-cushioned world of seat belts and airbags. Not that there is no real bad in the world, and she comes across that too, and is for that reason convinced that the man she now loves is better than most—if not the best—in both the worlds.

She finally finds a home for herself and also her man – the kidnapper – far from the ruthless world. And just when everything looks rosy and settled, a bullet presents itself on the scene and ends the kidnapper-villain-turned-hero. She is shocked and shaken, rejects the world, walks away to make her own world in the memory of her man at the same far away place. The credits roll.

The movie lacks novelty miserably. It treads a much beaten track, and what’s worse is that Imtiaz Ali has massively overdone all critical scenes and Alia Bhatt has failed to carry any of those scenes with any amount of conviction and ends up over-emoting every single time.

The first time she admits to Mahavir about being a victim of child abuse at the hands of her uncle, she goes over-dramatic to the extent that it loses much of its impact for anybody who has seen ‘Monsoon Wedding‘. The overly sudden warming up of Mahavir towards her after her admission of abuse looks out of sync with the angry, hardened character Mahavir is made out to be.

Her confronting her uncle and her mother over the abuse she suffered as a child in front of the entire family reminds one of Shefali Chhaya’s brilliant performance in a similar scene in Monsoon Wedding ; only Alia is not quarter as good as Shefali. And then the hysterical screams at the end aimed at displaying the suppressed rage in the girl is actually hilarious for the insufferable failure of the actor. Alia has tried too hard to act and the effort shows.

Her confronting her uncle and her mother over the abuse she suffered as a child in front of the entire family reminds one of Shefali Chhaya’s brilliant performance in a similar scene in Monsoon Wedding ; only Alia is not quarter as good as Shefali. And then the hysterical screams at the end aimed at displaying the suppressed rage in the girl is actually hilarious for the insufferable failure of the actor. Alia has tried too hard to act and the effort shows.

Perhaps Imtiaz Ali intended the hysterical screams of the heroine to convey her rebellious agony. Unfortunately, Alia fails miserably and ends up looking like a pampered kid throwing a tantrum. Besides, the cinematic device of using screams to display agony is a little loud and unless both the Director and Actor are very skillful and the scene really demands it, the output is bound to emerge jarringly loud. In this case, it is hopelessly flawed, too. Monsoon Wedding shows precisely the same thing in a much restrained fashion and leaves a lasting impact.

The sequence where Mahavir dies is similarly overdone. A much shorter version of the entire drama could create a much greater impact; if only the Director knew how to tell a story. The drama of Veera’s holding a dying Mahavir and trying to defend, lioness-like, her companion against a posse of armed policemen is melodramatic. Imtiaz Ali could simply show a sudden shot, an immediate death— like Bhiku Matre’s death in ‘Satya‘ — and a shell-shocked heroine, who undergoes a nervous breakdown and slips into silence. Nothing novel about that either, but it’s still a lot, lot better than the badly overdone melodrama that Imtiaz serves up.

Furthermore, why Mahavir had to be fatally shot anyway? The hostage and the lone, visibly unarmed kidnapper are around 20 feet apart with a clear, grassy field between them. In view of no immediate danger to the hostage, more than adequate opportunity to isolate the hostage, and surround, disable and capture the kidnapper, no trained task force in the world would shoot to kill. But Imtiaz Ali wants him dead for his own purposes and doesn’t mind shoving it down the throat of the audiences with a broomstick, which he does often enough to take away any cinematic merit that the movie could have otherwise had.

Originally published as part of my Legal Movie Review column LEGAL SCANNER in LAWYERS UPDATE [April, 2014 Issue; Vol. XX, Part 4]