Hatred is an effective long-term political tool because emotions are not resolvable issues. It sets the ball rolling down the slope with the ball gathering momentum on its own without requiring any more impetus till the time it hits a dead end, which is almost always a long way down the dark alley. Hatred wedges in a virtually indissoluble divide on the basis of perceived wrong and imaginary subjugation. It is a self-fueling machine that needs nothing more than a little push every now and then. It gives rise to new overzealous leaders, who just need to have a fiery tongue and a combative stand to exist regardless of whether or not they know the first thing about combat of any kind whatsoever. And, of course, the real issues can be put on the backburner to be attended to at leisure.

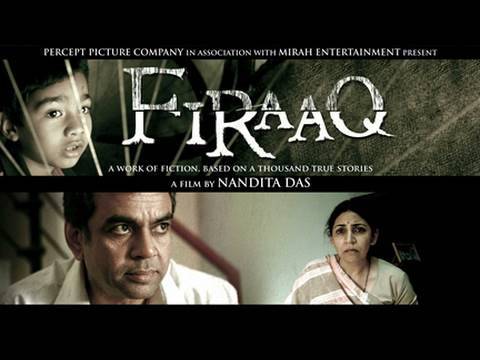

But then, the ‘installation’ of a divide is a painful process. So, when hatred is used as a political tool it has another side to it – the heart rending human side. Loss and tragedy is fodder to hatred, which keeps the masses divided. Firaaq focuses on this side of the story and tries to demonstrate how the ripple effect of hate-mongering touches all shores across the spectrum of economic prosperity and social status.

The movie begins with a roaring truck with an unmistakable lotus painted on the front of the hood dumping a huge load of bodies to be buried in what appears to be a mass grave reminiscent of Nazi Germany. Among the dead there is a Hindu woman. The very sight of the body enrages the middle aged grave-digger, who lunges on with a spade to kill the dead woman a second time. His younger companion holds him back as the older fellow breaks down in tears. That’s just the start of the harrowing journey into the lives of those who suddenly found themselves in the midst of a mindless massacre with little help in sight. They felt helpless and suspicious and desperately looked for someone whose collar they could hold and ask as to why they were made to go through blazing hell for not fault of theirs. And all through this the state stood by the sidelines and watched, disinclined to intervene. It wasn’t powerless; it never is. The state is always powerful enough to contain at will a bunch – no matter how large – of unruly hooligans. But it chose not to.

Firaaq zooms into the lives of five different people living their lives separately bound together only by common place and circumstances. Their stories just brush against each other. One thing common is that all of them have to deal with their circumstances against a violent backdrop in their own different ways. They are all baffled by the human tragedy that suddenly barges into their lives and they are left to fend for themselves. And this is just after the fire subsided with the after-heat very much present and perceptible.

Firaaq zooms into the lives of five different people living their lives separately bound together only by common place and circumstances. Their stories just brush against each other. One thing common is that all of them have to deal with their circumstances against a violent backdrop in their own different ways. They are all baffled by the human tragedy that suddenly barges into their lives and they are left to fend for themselves. And this is just after the fire subsided with the after-heat very much present and perceptible.

A Muslim couple returns back to their house from safety to find their humble abode burnt and ravaged. What lay there in tatters was the home they had built bit by bit for years. Who could have done this to them? Which of the neighbours? Nobody is above suspicion. Not even the wife’s closest friend, Jyoti, who comes to her with offer of work for her on her return. She must know who did this, the wife thinks and keep pestering her for answers while her husband is out looking for a gun to take revenge on one Mehul whose involvement the couple suspects because there was a dispute with him earlier. Of course, the suspicion is ill-founded and towards the end of the movie the quest for revenge would come to nothing with the couple realizing that they need to come to terms with their life as it exists.

A housewife (Deepti Naval) in a typical Gujarati family is feels forever guilty about not having sheltered some of those who came knocking fervently at their door begging to be protected from the bloodthirsty mob of killers. The rest of the family, however, goes about the business of living guiltlessly.

Then there is little Mohsin, a small orphaned child all of six or seven years of age who has run away from the ‘camp’ to look for his father. He learns from experience that when they ask your name, they want to know a little more than just the name. He also realizes that somehow Mohsin and Mohan were not just ‘two’ names, but were two ‘different’ names. And ‘Mohan’ was somehow ‘safer’ than ‘Mohsin’. That’s tragic and shameful for us as a nation.

Then there is little Mohsin, a small orphaned child all of six or seven years of age who has run away from the ‘camp’ to look for his father. He learns from experience that when they ask your name, they want to know a little more than just the name. He also realizes that somehow Mohsin and Mohan were not just ‘two’ names, but were two ‘different’ names. And ‘Mohan’ was somehow ‘safer’ than ‘Mohsin’. That’s tragic and shameful for us as a nation.

There is an old musician, Jageer Khan (brilliantly essayed by Naseeruddin Shah) who lives with his servant (Raghuveer Yadav’s effortless marvel). The musician refuses to accept the communal divide and considers it a human problem. Towards the end he almost loses hope for a little while and feels that everything, including music, was powerless to subdue such hatred. But then, the next day he is back to his polished notes. Hope refuses to sink.

A Hindu-Muslim couple decides to leave for Delhi after their store is robbed during the riots. But the husband, Sameer Sheikh (Sanjay Suri), despite being scared is uncomfortable with the fact that he has to leave. He also realizes to his utter discomfort that going to Delhi was not the solution because no matter where he goes, Delhi or Delaware, he remains Sameer Sheikh and would be looked upon with suspicion on account of his religious identity. So, at the end he decides to stay where he belongs.

The movie ends on hope. Yes, there is hope. There is hope that the life can still continue. But that is not enough. We are still to glimpse the hope that burnt bridges could and would be rebuilt.

The more worrisome side of Gujarat pogrom has been the state complicity, which is undeniable. It was not a failure of law and order machinery, but a misuse of it for political mileage. Secularism is part of the basic structure of the Constitution and of our collective aspirations set out in the Preamble itself

A flagrant violation of a fundamental constitutional principle by a political entity that has sworn allegiance to the Constitution it later chooses to violate and subvert, cannot be taken lightly. And if, for any reason whatsoever, we as a nation fail to hold such an entity accountable, it is a collective failure of the people. And failures of such humungous proportions have unbearable consequences.

Originally written for and published in LAWYERS UPDATE (June Issue; Vol. XV, Part 6)