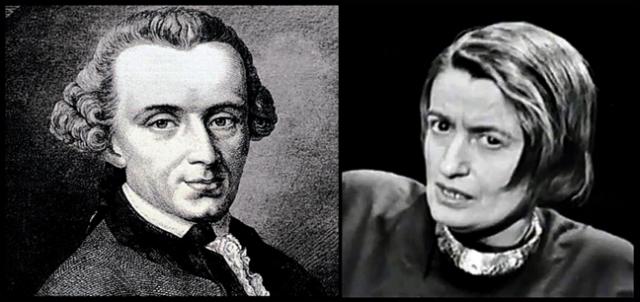

Ayn Rand was extremely critical of Immanuel Kant. She considered him her intellectual adversary and found him standing against everything that she and her philosophy stood for. Therefore, she found it necessary to attack Kant’s ideas. She strikes Kant’s views regarding the limitations of reason thus:

He [Kant] did not deny the validity of reason – he merely claimed that reason is “limited,” that it leads us to impossible contradictions, that everything we perceive is an illusion and that we can never perceive reality or “things as they are”. He claimed, in effect, that the things we perceive are not real because we perceive them. [ Philosophy: Who Needs It ;p. 64, emphasis original]

We receive information through sensory inputs and then the information is quickly interpreted and processed by the brain and we reach certain conclusions regarding the received information. It cannot be conclusively said that the information received by the senses is complete in the sense of containing everything that is required for the reason to completely comprehend the truth about the object perceived. Besides, reason also uses certain tools to comprehend the sensory input and the tools would have certain inherent limitation because it is in the nature of the tools to be informed by purpose. Our understanding of objects is conceptual and objective because reason classifies things in terms of categories already grounded in our understanding. In short, when the object translates into our understanding of it, something is lost in translation, which is why our understanding remains incomplete and deficient. That’s what Kant means.

Kant does not say that what we perceive is not true but simply says that it is not the whole truth and therefore it is not ‘the truth’ because if we only know something about an object and not everything, we actually do not ‘know’ the object as it actually is but only have an idea of it, which is open to correction.

Kant does not say that what we perceive is not true but simply says that it is not the whole truth and therefore it is not ‘the truth’ because if we only know something about an object and not everything, we actually do not ‘know’ the object as it actually is but only have an idea of it, which is open to correction.

For instance, you see a cow from a certain distance. You are sure that it’s a cow. You go closer and you find that it looks more like a goat and so it is a goat. You go closer still and realize that the object is not moving at all and if it were a goat, it should have shown some movement. So, it is possible that it is an inanimate object resembling a goat. Perhaps, it is a large rock that looks like a goat. When you are standing right beside it and so close as to say what it actually is, you find that it is a man sleeping with a whitish sheet over him on a bench made of concrete. All this while you received sensory inputs and your brain tried to match the images received with the already stored images and associated ideas, and you kept correcting your perception and understanding of the object. Now, you feel you are close enough to pass a conclusive judgment on what the object really is. When there have already been so many corrections in your perceptions and each correction changed your understanding of the object completely, what makes you think you are close enough to conclusively say that what you now perceive is ‘the whole truth’ about the object?

Reason and logic have always been scientists’ indispensable tools, but scientific theories have always been open to challenge and correction and many of the scientifically tested ‘facts’ had to be corrected on account of later findings. It says something about the limitations of reason that is not very different from what Kant believed. About the limitations of perception Einstein says:

We all start from “naive realism,” i.e., the doctrine that things are what they seem. We think that grass is green, that stones are hard, and that snow is cold. But physics assures us that the greenness of grass, the hardness of stones, and the coldness of snow are not the greenness, hardness, and coldness that we know in our experience, but something very different. The observer, when he seems to himself to be observing a stone, is really, if physics is to be believed, observing the effects of the stone upon himself.

So, Rand’s attack on Kant’s understanding of the limitations of reason does not seem to be as successful as she would like it to be.

Rand is also at war with Kant’s conception of morality. She criticizes Kant’s morality thus:

What Kant propounded was full, total, abject selflessness: he held that an action is moralonly if you perform it out of a sense of duty and derive no benefit from it of any kind, neither material nor spiritual; if you derive any benefit, your action is not moral any longer. [Philosophy: Who Needs It ; p. 65; emphasis original]

So, you do something for someone in order to derive some benefit in return. It’s a trade off. There is no morality involved in it. The person is not motivated by any moral consideration whatsoever but by the desire to gain something in exchange. Therefore, the action is certainly not moral, but that does not make it unworthy or immoral. It is simply amoral because when it is about a mutually beneficial exchange, morality steps out of the equation.

Furthermore, Kant also makes a distinction between the deeds done ‘from’ duty and ‘in accordance with duty’. If a person is bound by duty to assist people and does not do that, he is not acting in accordance with this duty. Suddenly, he spots someone who he feels needs help badly, he rushes forth and helps the fellow out. He has acted ‘in accordance with’ duty but not ‘from’ duty because the person did not act with a sense of duty. Now, if the same person helps others simply because it is his duty to do so, he acts ‘from’ duty. Kant opined that what is done ‘from’ duty is essentially moral.

Furthermore, Kant also makes a distinction between the deeds done ‘from’ duty and ‘in accordance with duty’. If a person is bound by duty to assist people and does not do that, he is not acting in accordance with this duty. Suddenly, he spots someone who he feels needs help badly, he rushes forth and helps the fellow out. He has acted ‘in accordance with’ duty but not ‘from’ duty because the person did not act with a sense of duty. Now, if the same person helps others simply because it is his duty to do so, he acts ‘from’ duty. Kant opined that what is done ‘from’ duty is essentially moral.

Again, the ‘duty’ mentioned above has to be something for which the person is not being ‘paid’ because if he is being paid to do something, it is a quid pro quo , in which case morality is not involved.

When Ayn Rand declares that selfishness is moral, she is actually emphasizing that it is ‘not immoral’ to be selfish and one must not be apologetic or feel guilty about it. To be selfish one doesn’t need any moral sanctions or considerations; one needs morality to act unselfishly. Kant is simply pointing that out. Therefore, Rand’s criticism of Kant on that front, too, fails to convince.

Rand wishes to establish the superiority of reason primarily because the moment one concedes that reason has its limitations and perceptions and understanding could be flawed, and that something could stand beyond reason and human understanding, it becomes possible for one to sneak in things like faith and ‘collective aspirations’, which Rand sees as downright evil and is dead against.

Originally published as part of Thinkers and Theory series in Lawyers Update in June 2011.