On April 10, 1919, a demonstration was staged at the residence of the Deputy Commissioner of Amritsar, Punjab, demanding the release of two popular leaders of the Indian Independence Movement – Satya Pal and Saifuddin Kitchlew. The two were part of Mahatma Gandhi’s Satyagraha movement and had been arrested in that connection by the British Government. They were held at a secret location. The demonstrators were shot at by a military picket and several protesters were killed. This led to several violent incidences with several banks and other government buildings damaged and set ablaze. The violence escalated and ended up claiming the lives of five Europeans, including government employees and civilians. By April 13, 1919, due to large scale violence, the government had brought much of Punjab under martial law, which restricted civil liberties and suspended freedom of assembly, as a consequence of which an assembly of more than four people was prohibited.

In Amritsar, on the day of the festival Vaisakhi ( Baisakhi ) on April 13, 1919, thousands of people including Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims gathered near the Harminder Sahib in Jallianwala Bagh. The meeting was scheduled to start at 4:30 PM, and did start on time. An hour later, at around 5:30 PM, Brigadier-General Reginald E.H. Dyer entered the Jallianwala Bagh with ninety (90) soldiers (twenty-five Baluchi and sixty-five Gurkha soldiers), out of which fifty (50) carried rifles and there were some machine guns, too. The main entrance was blocked by soldiers with the armoured vehicles standing behind them outside the gate, as the vehicles could not enter the place. The troops were ordered to open fire with the intention – as Dyer later explained – to not “disperse the meeting but to punish the Indians for disobedience”. Some 1650 shots were fired. And the British inquiry placed the number of killed at 379 while a separate inquiry instituted by the Indian National Congress claimed that over 1000 died and over 1500 were injured.

Some four decades after Jallianwala Bagh, another incident reminiscent of Jallianwala took place in another part of the world amidst similar, on-going non-violent movement. It’s called Sharpeville Massacre, and took place on March 21, 1960 at a police station in the township of Sharpeville in South Africa.

In 1923 a certain kind of enactments called the ‘Pass Laws’ were brought in force in South Africa. These laws were meant to keep the blacks and the non-blacks separate and to limit the movement of the non-white populace. The non-white people – the blacks basically – were supposed to carry the ‘passbooks’ issued to them whenever they moved out of the designated ‘homelands’. The passbook was a documentation proving that they were authorized to move or live in the “White” South Africa. A failure to produce the passbook could – and often did – result in the arrest. Any white person, even a child, could ask a black person to produce his or her passbook. The simmering discontent over this highly discriminatory law climaxed in Sharpeville, when the black demonstrators protesting against the ‘Pass Laws’ were fired upon by the South African police resulting in the death of 69 people on March 21, 1960.

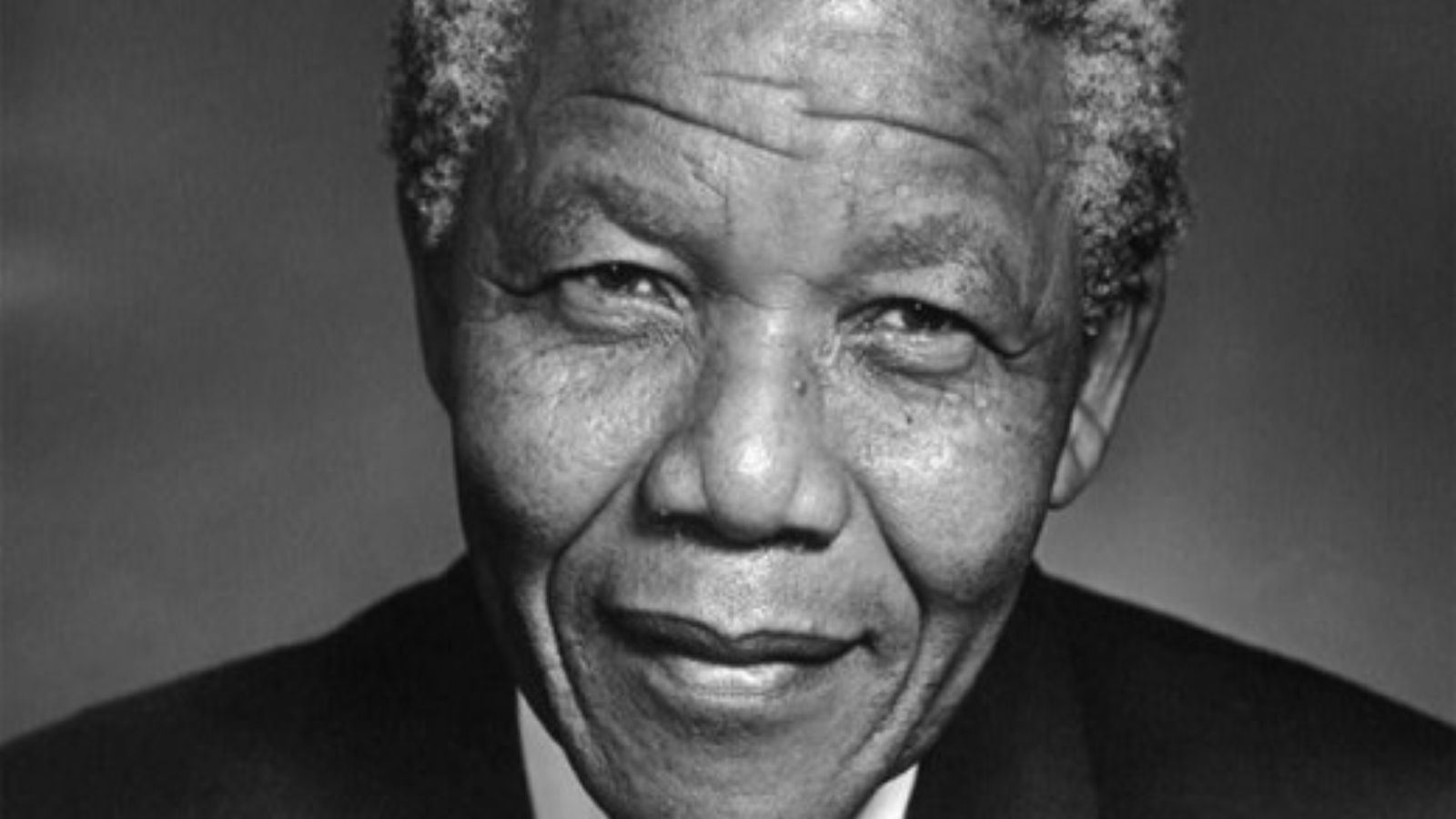

The Sharpeville Massacre and the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre are remarkably similar in many ways. They occupy a central position in the non-violent struggles against discrimination in South Africa and India respectively. While at the center of Sharpeville was the legendary South African leader, Nelson Mandela, Jallianwala Bagh was an event that surrounded Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent movement against the British occupation of India. Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence inspired both Mandela in South Africa as well as Martin Luther King, Jr., in the United States. In both Sharpeville and Jallianwala, the armed forces fired upon the innocent, unarmed protesters. However, more than the similarities it is the dissimilarities between the two events that are interesting.

At Sharpeville, the protests started at around 10:00 in the morning with a large crowd, but the atmosphere remained peaceful and festive with fewer than 20 police officers around, and then the crowd started to grow and soon enough there were 19,000 protesters around, and the atmosphere started turning hostile with the agitated mob turning “insulting, menacing, and provocative”, which necessitated the calling in of some 130 police personnel supported by four Saracen armoured cars as reinforcement. The protesters started getting violent hurling stones when Sabre jets and Harvard Trainers approached the ground flying low over the place so as to scatter the crowd. The protesters repeatedly attempted to dash the police barricades. After tear gas failed to have any effect, the policemen had to use their batons to defeat the advances by the crowd. At around 1:00 in the afternoon, the police attempted to apprehend the leader of the group resulting in a scuffle that made the crowd surge forward. Reportedly, at least two of the police officers ordered their men to load their firearms but also ordered them to use the arms only in case of dire emergency. Protesters started screaming, reached the fence and tore the gates from the hinges, one of the police commanders was knocked to the ground and stones were thrown at the other. It is then that the shooting began.

Jallianwala Bagh massacre was Brigadier-General Dyer’s way of “punishing the Indians for disobedience”, as he himself admitted, but Sharpeville massacre was by and large a result of police officers’ pushing the panic button a little too hard resulting in the application of hugely disproportionate force. It wasn’t exactly an act of calculated violence to accomplish compliance of orders and fearfulness of the regime like the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. It was more in the nature of defence than attack.

An interesting contrast emerges when we look at the two events side by side. Jallianwala Bagh occurred nearly half a century before Sharpeville, and was actually a viciously brutal and violently suppressive act aimed at disciplining the subject people of the British empire, if Dyer’s candid admission is anything to go by, but even then it did not shake the faith of Mahatma Gandhi in the non-violent means of protest. Sharpeville massacre, on the other hand, wholly lacked the vicious cruelty of Jallianwala Bagh massacre. And despite knowing that Mahatma Gandhi’s unfaltering faith in non-violence had finally gone a great way in securing independence for India from a hostile colonial power, Sharpeville shook Nelson Mandela’s faith in non-violence, and in a statement made before the Supreme Court of South Africa on April 20, 1964, Mandela said:

We of the ANC had always stood for a non-racial democracy, and we shrank from any action which might drive the races further apart. But the hard facts were that 50 years of non-violence had brought the African people nothing but more and more repressive legislation, and fewer and fewer rights. By this time violence had, in fact, become a feature of the South African political scene….Each disturbance pointed to the inevitable growth among Africans of the belief that violence was the only way out – it showed that a government which uses force to maintain its rule teaches the oppressed to use force to oppose it.

I came to the conclusion that as violence in this country was inevitable, it would be unrealistic to continue preaching peace and non-violence. This conclusion was not easily arrived at. It was only when all else had failed, when all channels of peaceful protest had been barred to us, that the decision was made to embark on violent forms of political struggle. I can only say that I felt morally obliged to do what I did.

Originally written for and published in LAWYERS UPDATE in three parts as a part of ‘THE LAW AND THE CELEBRITIES‘ series in February 2013.