A citywide boycott of public transit was called for by the MIA with King in the lead. They did not demand complete integration of the black and the whites to begin with. All they wanted was that the provisions of the law be changed to the effect that if the portion of the bus allotted for the whites was full, the blacks were not asked to stand up and let the whites have their seats. So, in case of over-subscription of seats in the section for the whites, the whites were to stand and not the blacks. The boycott leaders believed that this would be easier to concede for the city of Montgomery than complete integrations.

The support for the boycott was phenomenal right from the beginning. Rosa Parks was arrested on December 1, 1955, and from December 3, 1955, almost no blacks were boarding the transit buses any more. The boycott caused a sharp dip in the number of the bus riders causing substantial loss to the transit system of the city. The blacks took to walking, cycling and arranging carpools to travel. The black car owners were more than willing to lend support. The city attempted to foil the boycott by pressurizing the local insurance companies to not insure cars used in the carpools, which made the leaders of the boycott approach Lloyd’s of London to procure insurance for such cars. When black taxi drivers started charging the blacks the same amount (ten cents) for the ride as the bus ride cost, the city officials responded by ordering fine against any cab driver who charged below 45 cents per ride. The churches for the blacks across the nation started raising money to support the boycott. Even the less-used shoes were collected and sent to the black residents of Montgomery because they walked around so much instead of taking bus rides and thus refused to submit to Jim Crow laws.

The whites were much in opposition to the boycott, quite naturally, and the membership of the White Citizens’ Council doubled during the boycott. Violence among the blacks was also not infrequent with boycotters subjected to physical attacks, and Martin Luther King’s and Ralph Abernathy’s houses firebombed in addition to four black Baptist churches suffering the same fate. 156 protestors were rounded up under the 1921 ordinance for “hindering” a bus. King was among the arrested. He was directed to pay a fine of $500 or serve 386 days in prison, King refused to pay up and was kept in prison for two weeks. “I was proud of my crime. It was the crime of joining my people in a non-violent protest against injustice,” King would later say. Imprisoning King backfired attracting nationwide attention to the protest.

With the national focus on the protests, the pressure started mounting by each passing day and on June 4, 1956, the federal district court struck down Alabama’s racial segregation laws for buses as unconstitutional, but with the appeal pending, the laws continued to operate and the boycott continued as well. Finally, on November 13, 1956, the Supreme Court rejected the appeal and upheld the judgment of the district court. In the wake of the Supreme Court verdict, the city passed an ordinance allowing black passengers to sit anywhere on the bus. The boycott was officially terminated on December 20, 1956 having lasted for 381 days.

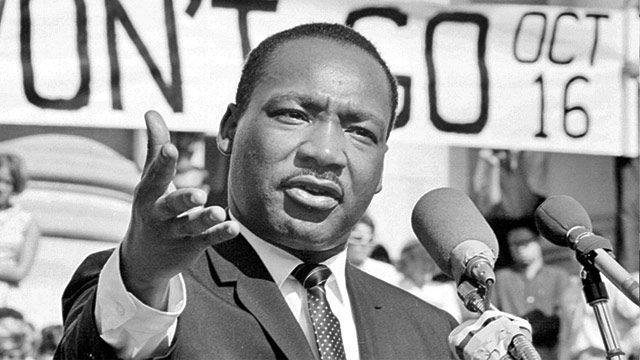

The Montgomery Bus Boycott brought one of its first victories for the Civil Rights Movement and brought Martin Luther King, Jr. to national attention.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott brought one of its first victories for the Civil Rights Movement and brought Martin Luther King, Jr. to national attention.

A group called the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was formed in 1957 by King, Ralph Abernathy, and other civil rights activists to better utilize the moral authority and organize the power of black churches to conduct non-violent protests in pursuance of the Civil Rights Reform with King as its head. King continued to lead the SCLC until his death in 1968.

After the Montgomery Bus Boycott, it was the Albany Movement that King got involved with in December 1961. The Movement launched non-violent protests against all aspects of racial segregation. King was in town on December 15, 1961, and had planned to be there for a day, give counsel and return home. However, things turned out differently when the next day peaceful protestors were arrested. King courted arrest and declined bail until the city relented to make concessions. The agreement was reached, but the city failed to meet its side of commitments, following which King returned in July 1962, and was handed down a sentence of forty-five days in jail or a $178 fine. The choice was his, and, like earlier, he chose jail. However, his fine was discreetly arranged by the city authorities and he was released.

Reacting to the unwanted release, King said, “We had witnessed persons being kicked off lunch counter stools during the sit-ins, ejected from churches during the kneel-ins, and thrown into jail during the Freedom Rides. But for the first time, we witnessed being kicked out of jail.” The Movement continued for almost a year, but did not bear the desired fruits, and started to deteriorate with incidents of violence by the protestors coming to light. King asked the demonstrations to be brought to a halt and called to observe a “Day of Penance” in deference to the spirit of non-violence. However, the Movement, by and large, failed to achieve much on account of the divisions within the black community coupled with little response from the local authorities. Nevertheless, the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement learnt crucial lessons in tactics from the failed movement.

The Birmingham Campaign, which was the next battle in the racial desegregation war, succeeded fundamentally because the lessons learnt from the failed Albany Movement were wisely applied. Therefore, unlike Albany Movement, the focus in the Birmingham Campaign was narrowed down to the clearly defined goals of making the hiring practices in the city employments fair to the blacks and taking steps to dilute racial segregation in the city where such segregation was among the sharpest in the country. The black citizens faced legal and economic disparities and had to stand violent retribution if and when they tried bringing their problems into focus. Therefore, the Birmingham Campaign involved protests to pressurize the business leaders in the city to provide equal opportunities to all races and also to put an end to segregation in the use of public facilities, restaurants, and shopping stores.

Originally written for and published in LAWYERS UPDATE in three parts as a part of ‘THE LAW AND THE CELEBRITIES‘ series in August 2012.