A landlord who owned a house on Kossuth Street in Cinkota within the jurisdiction of Budapest, Hungary, called Dr. Charles Nagy, Detective Chief of the Budapest Police, in July 1916, and shared his suspicion that his aforementioned property could be the site of murder. The landlord told the detective that he had rented the house to a soldier called Bela Kiss, and the lease had lapsed with no attempt from Bela Kiss to have it renewed. The landlord also told that Kiss was rumoured to have been captured by the enemy in a battle, or might have been killed in a battle. The landlord had gone over to his property to see if some repairs were needed before the property was ready to be rented out again. He found several large metal drums kept outside the house, and when on puncturing one of the drums an unbearable stench ensued, he asked a chemist living next door for advice and the chemist told him that the unbearably foul smell of that kind could only come from a decomposing human body. So, the landlord decided to hand the matter over to the police.

Nagy travelled to the little town of Cinkota to investigate the matter with two of his best detectives. When he reached the property an aged Mrs. Jakubec, who had been employed by Bela Kiss and left behind to take care of his belongings, was pretty much angry about the police intrusion. But that did not deter the officers from having the metal drums opened, which confirmed the landlord’s suspicion. Each of those drums carried the naked dead body of a young woman. The wood alcohol in which the bodies were put was the preservative the killer had chosen to use. All victims had died of strangulation. The bodies were quite well preserved and could be easily identified provided one had a few names to begin with, which the police did not have then.

It was the most important case in Detective Chief Nagy’s working life, which is why he did not want to take any chances of any kind. Therefore, he acted very carefully and methodically. Since Bela Kiss was a Hungarian solider, the armed forces were informed about the case with the request that Bela Kiss be apprehended and handed over to the police. The manhunt was immediately launched. He apprehended the housekeeper immediately so that he could know all that she knew about Bela Kiss and the bodies in the metal drums. The postal and telegraph authorities were also told to hold on to any communication meant for Bela Kiss.

In normal circumstances getting hold of Bela Kiss could not have posed as much difficulty as it did because thousands of Hungarian soldiers were under detention at different locations, the army was not organized on account of the war, and ‘Bela Kiss’ was a very common Hungarian name.

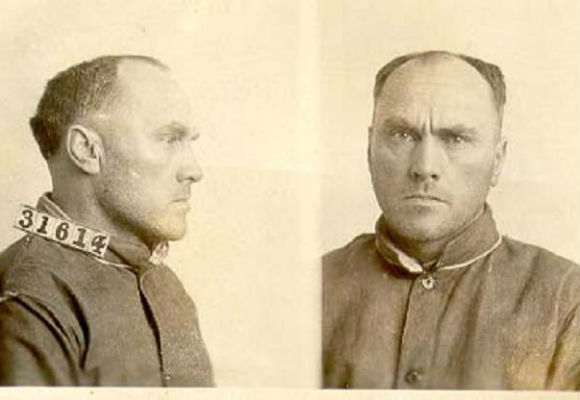

While Bela Kiss was being looked for all over, Nagy’s investigation revealed that in the early 1900s, a young and fairly handsome Bela Kiss had rented this house at 9 Kossuth Street on the outskirts of Cinkota, a town right at the edges of Budapest. He was a tinsmith, but at the age of 37 he was drafted into the armed services in 1914. Kiss had done well as a tinsmith and being the voracious reader that he was, he was capable of holding a conversation about virtually everything despite never having attended school. So, to his fellow villagers he was a self-educated, hard-working, amiable young man, which also made him one of the most eligible bachelors around.

However, he was in no hurry to tie the knot. In Mrs. John Jakubec he had found an elderly, good-natured woman for a housekeeper to take care of the house and things like cleaning and food.

Cinkota did not offer a lot in terms of women. So, Kiss brought out advertisements in newspapers in Budapest and also maintained an apartment there. Women started corresponding with Kiss and people noticed that some pretty women came over from Budapest for short durations to Cinkota to spend time with Kiss. But none of the women were introduced to anybody from Cinkota including Mrs. Jakubec.

Cinkota did not offer a lot in terms of women. So, Kiss brought out advertisements in newspapers in Budapest and also maintained an apartment there. Women started corresponding with Kiss and people noticed that some pretty women came over from Budapest for short durations to Cinkota to spend time with Kiss. But none of the women were introduced to anybody from Cinkota including Mrs. Jakubec.

When Kiss brought the metal drums, it raised suspicion and curiosity among the people and some suspected that Kiss could be illegally storing army liquor in those drums. The talk among the locals led to a Cinkota constable’s taking it up with Kiss, who assured the constable that the metal drums were not meant for storing stolen liquor, but were meant for stocking gasoline in view of the war. The matter was thus laid to rest.

Without identifying the victims it was not possible to get to the bottom of the case, as the answer to the question of motive could only be found when the identity of the victims and their connection with Kiss was known. Metal containers provided no clue. An embroidered ‘K.V.’ on one piece of clothing and an ‘M.T.’ on a handkerchief were the only clues found. The police looked into the house thoroughly but nothing relevant to their investigation could be found until they chanced upon a locked door. Mrs. Jakubec informed Nagy that it was the secret room that Bela Kiss kept for himself and she had been instructed to neither enter the room, nor let anyone in though Mrs. Jakubec did have the key to the room.

The room was opened and a massive volume of correspondence between Kiss and several women was found together with an album with the pictures of over hundred women. Hundreds of letters were arranged in 74 different packets so as to keep the correspondence with each woman in single, separate place to prevent mix up.

The letters also revealed that Kiss had defrauded the women of their savings and in many cases their entire financial resources were exhausted. Some of the letters were written as far back as 1903.

How did nobody get suspicious of so many women coming to see Kiss? When Nagy talked to the people, he found that everybody liked Kiss and none found it unusual for a handsome, well-spoken man to entertain a good number of women at his residence. Quite understandably, most married men envied Kiss.

Nagy got in touch with all such police departments under the jurisdiction of which fell the areas where the letters written to Kiss were sent from. And eventually he managed to draw certain conclusions. When his carefully worded newspaper advertisements drew the attention of a woman living not too far away and she chose to respond, Kiss would pay her a visit and drench her in care, affection and expensive gifts. With faith in Kiss cemented by his charm and affection, a promise of marriage led to the woman lending a financial helping hand to build a home and life with Kiss. And the money would start coming in from the woman. Sooner or later a time would come when the woman would get to know the truth about the actual intentions of Kiss and as soon as she became something to fear for Kiss, he would arrange to eliminate her. He purposely choose the woman who did not have any close relative living close by, which ensured the lady would not be missed immediately after her disappearance.

Nagy’s efforts paid off when he could finally connect the initials ‘K.V.’ to Madame Katherine Varga, a pleasant looking, young Budapest widow, who ran a profitable dressmaking business, which she had sold to start new life with her future husband Bela Kiss in Cinkota. That never came to pass, and when she disappeared, she did not have any relative to worry about or look for her.

Another breakthrough came when Nagy managed to identify another woman who came in contact with Bela Kiss the same way as others. A detective assisting Nagy went through the old court records and found that there were two women – Julianne Paschak and Elizabeth Komeromi – who had sued Kiss for cheating them of money by promising marriage. However, both the suits lapsed because neither of the women appeared in the court and could not be contacted.

By now, Nagy had gathered sufficient evidence to prove that Kiss had killed some 30 women, but only one of the victims among the seven found in the canisters could be identified. That changed when two women – Mrs. Stephen Toth and her daughter-in-law – came looking for one Margaret, the daughter of Mrs. Toth. Margaret had come to Budapest in search of work. And on one of her visits to her daughter, Mrs. Toth had met Bela Kiss and had also been persuaded by Margaret to give some money to Kiss. Margaret had told Mrs. Toth that Kiss had promised to marry Margaret. The promise was not fulfilled and Margaret accused Kiss of going back on his word. When Margaret did not contact her mother for some time, she went to Cinkota looking for Margaret and confronted Kiss, who told her that he just wanted to delay the marriage, which got Margaret angry and she left for America.

By now, Nagy had gathered sufficient evidence to prove that Kiss had killed some 30 women, but only one of the victims among the seven found in the canisters could be identified. That changed when two women – Mrs. Stephen Toth and her daughter-in-law – came looking for one Margaret, the daughter of Mrs. Toth. Margaret had come to Budapest in search of work. And on one of her visits to her daughter, Mrs. Toth had met Bela Kiss and had also been persuaded by Margaret to give some money to Kiss. Margaret had told Mrs. Toth that Kiss had promised to marry Margaret. The promise was not fulfilled and Margaret accused Kiss of going back on his word. When Margaret did not contact her mother for some time, she went to Cinkota looking for Margaret and confronted Kiss, who told her that he just wanted to delay the marriage, which got Margaret angry and she left for America.

Nagy figured what actually happened. In 1906, when Margaret Toth visited Kiss in Cinkota, he compelled her to write a letter to her mother stating that she couldn’t bear rejection by Bela Kiss and was leaving for America in search of new life. Once the letter was written, Kiss killed her, stored her body in one of the metal canisters, and posted the letter to Mrs. Toth.

On October 4, 1916, Nagy received a message from a Serbian hospital informing him of the presence of a Hungarian soldier called Bela Kiss. But by the time Nagy reached, the news of his coming found its way to Kiss, who escaped leaving another solider in his bed. After that there were many supposed sightings, but Bela Kiss was never caught.

Originally written for and published in LAWYERS UPDATE as ‘Crime File’ in February 2013.