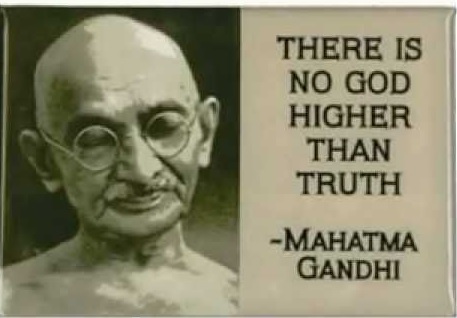

Mahatma Gandhi, a lawyer by training, had his political and legal worldview rooted firmly in his conception of moral uprightness with truth and non-violence at the very core. This makes understanding him tricky because his views are not strictly political or legal but are part of a composite whole. He looks at life in entirety. To his mind one’s political life is not exclusive of one’s social, moral or spiritual life. In other words, he does not see life in terms of watertight compartments with different approaches to different aspects.

This remarkable feature is admirably brought out and explained by Professor Akeel Bilgrami, a noted political philosopher and Johnsonian Professor of Philosophy at Columbia University, in his much admired work, Gandhi’s Integrity: The Philosophy behind the Politics.

Akeel Bilgrami concedes upfront that after making an effort to understand Gandhi, one is almost never sure if one has understood the Mahatma correctly, which is primarily because Gandhi’s thoughts and opinions are highly integrated, which makes it impossible for one to understand his political opinions or social opinions without understanding the crux of his moral standpoint, which might also have some reference to his religious views. So, Gandhi’s thoughts must be understood in totality.

Bilgrami turns to Gandhi’s strategy of non-violent political resistance, and notes that while in the West non-violent political protest was used to gain greater say in the governance of the country within the legal framework, Gandhi, in India, used non-violent resistance as a tool to mobilize people. The other two options were to support the elitist attempt to engage in dialogue with the rulers to have a better say or to resort to extremist violence, and both of these failed to mobilize the common man because he could not relate to either.

Gandhi did not believe that violence could be used to attain long-term peace. Gandhi’s Satyagrahi was to be moral exemplars and not activists with some ideology to pursue.

Gandhi did not believe that violence could be used to attain long-term peace. Gandhi’s Satyagrahi was to be moral exemplars and not activists with some ideology to pursue.

Getting the British out was the primary objective for the Mahatma. He wanted the slavery that came with the British ideas and institutions out. In his opinion so long as the British ideas remained Indians would remain subject people despite the departure of the British. So, he wanted to bring in the Indianness back to India and the Indians to replace British ideas.

Bilgrami also notes that Gandhi’s strategy of non-violence is not simply a political tool, but is part and parcel of his search for the truth. Bilgrami compares J S Mill’s and Gandhi’s conceptions of truth, and finds that Mill felt that since we could never be certain about the truth because a number of previous ‘truths’ have been found false, we must be tolerant of disagreements.

But this is not the same line of thinking that Gandhi takes despite advocating tolerance as forcefully as Mill does. Gandhi advocates tolerance because to him imposition of one’s views on others is a form of violence. Gandhi’s Satyagrahi is a seeker of truth, which means that to him truth is not unattainable because if it were so, there would be no point in even trying to attain it. Unlike Mill’s tolerance of disagreement, Gandhi’s tolerance is not based on the uncertainty of truth but on not refusing to impose the truth on others because such imposition would be a violent act in itself.

Any political thinker in liberal tradition would consider public criticism indispensable to a healthy political system with effective self-corrective mechanism in place. However, Gandhi thinks otherwise, for he sees criticism as inherently violent, but does not find the same for resistance. He is of the opinion that one could resist with a ‘pure heart’ and without being violent but criticism is not possible without ‘hostility’, which is just another form of violence.

Another remarkable feature that Bilgrami points in Gandhi’s thought is the limits he places on the ‘universalizability’ of moral judgments. Universalizability is different and distinct from ‘universality’, for the former means that a moral principle can be extended to all placed in a certain situation, and those who do not hold them valid or refuse to conform commit an act of immorality because it is not possible to say that there can be something that is morally right but some people may think otherwise without being wrong. Therefore, Gandhi implicitly rejects the idea that it is not possible to not criticize someone who does not believe in or conform to the morally right, which means he refuses to allow the notion of universalizability of morality to interfere with his tolerance of disagreement.

Bilgrami says that in the slogan ‘when one chooses for oneself, one chooses for everyone’, Gandhi subscribes to the first part but not to the second. To him, when one chooses for oneself, one sets an example for others, which others may or may not follow. By choosing for oneself, one does not lay down a moral principle that needs to be necessarily adhered to, but simply sets an example.

Bilgrami says that in the slogan ‘when one chooses for oneself, one chooses for everyone’, Gandhi subscribes to the first part but not to the second. To him, when one chooses for oneself, one sets an example for others, which others may or may not follow. By choosing for oneself, one does not lay down a moral principle that needs to be necessarily adhered to, but simply sets an example.

By rejecting categorical imperative and universalizability maxim, Gandhi manages to avoid moralizing against others and sidesteps the necessity to criticize.

The idea of moral exemplar was perhaps at play when Gandhi talked of smaller communities because it is easier to set an example in small societies than big cities, which is also why he considered migration to big cities detrimental to moral life.

Gandhi’s morality has ‘truth’ at its heart, which also means that truth, the way Gandhi looks at it, is central to his thought. According to Bilgrami, Gandhi’s truth is not a cognitive notion but an experiential one. Truth does not lie in our faithful description of the world but in our moral experience of it. Gandhi, therefore, refuses to let the world be reduced to an object of study because that would lead to the laying down of moral principles, the violation of which would invite adverse action resulting in violence of one kind or the other.

Bilgrami attempts to show that for Gandhi pursuit of truth is much the similar thing as ‘truth-telling’, and here Gandhi makes the mistake of collapsing the cognitive value of truth into the moral value of truth-telling. According to Bilgrami, it is not the truth-teller or the liar that fails to value the truth, but the one who is prepared to speak and write without any willingness to get things right.

Bilgrami points out that Gandhi was convinced of the inherent corruptibility of our moral psyche, which is why he feared that intellectualization of truth in the sense of stressing cognitive value would lead to alienation from nature and would make us pursue self-destructive goals. Therefore, there is a certain amount of pessimism inherent in the integrity of Gandhi’s thought.

However, given the selfish nature of man, the suspicion is quite natural and Gandhi is joined by a good number of great political thinkers in this regard from Plato to Kautilya.

Originally published as part of Thinkers and Theory series in Lawyers Update in July 2012.