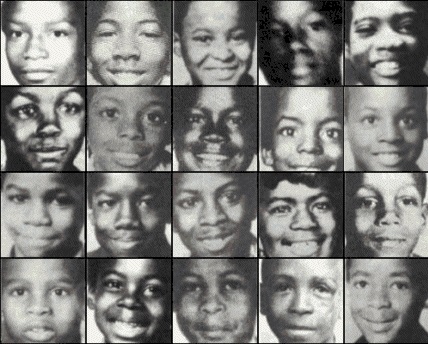

The odd thing about the Atlanta Murders or ‘the missing and murdered children case’, as it is called locally, is that despite having an accused who was found guilty and who might have been responsible for a few of those deaths, we still don’t know if the guilty has or have been brought to book.

Furthermore, it is very almost certain that the man convicted of two of those murders did not kill as many as 28 African-American children in around two years between 1979 and 1981. It seems that the police messed up the investigation and even the FBI could not really get everything right. And to complicate things further, the defence did not have the time or the resources to put up the defence required to ensure that the accused was not convicted until and unless his guilt had been proved ‘beyond reasonable doubt’.

On July 21, 1979, around midnight, Edward Hope, a fourteen-year-old who lived on Cape Street in Southwest Atlanta in one of the housing projects, was on his way back from a skating rink after having spent the evening with his girlfriend when he disappeared. And a few days after, one of his friends, Alfred Evans – another 14-year-old – also disappeared. Evans lived on the other side of town off Memorial Drive in the East Lake Meadows housing projects, and, being a karate enthusiast, had gone to watch a karate movie in downtown Atlanta, and never got back home.

The dead bodies of both Hope and Evans were found on July 28 near Niskey Lake Road in the southwestern part of the city. Hope had been fatally shot with a .22-caliber gun while the cause of Evans’ death could not be determined though the medical examiner thought that he died of asphyxia resulting from strangulation. Both of them were wearing black clothes. However, Hope’s socks and football shirt were not found while Evans was wearing a belt that was not his. Another problem was that while Hope’s identification was easily done by his dental records, Evans’ identification is still under question. So, whether the other dead body was Evans’ or not is still under the shadow of doubt.

It was found that the boys had some involvement with drugs, which could be a cause of some struggle that resulted in their death. That happened all the time. So, the police did not make much of it. The investigation was not rigorously pursued. Drugs and death are close relatives. But no such association could be found in case of Milton Harvey – another 14-year-old. Harvey had borrowed a bike and had gone to a bank to pay the credit card bill for his mother when he disappeared to be found dead in mid-November in a rubbish dump off Redwine Road in the suburb of East Point. The place where Milton’s badly decomposed remains were found was outside the jurisdiction of Atlanta city while the bicycle that he had rode off on was found a week after his disappearance on Sandy Creek Road, a deserted dirt lane.

A week before Milton’s disappearance, Yusef Bell (9) had disappeared. His body was found on November 8, 1979 in a concrete hole in the floor of an abandoned school building. Unlike the earlier killings, this one caught media attention, and gathered such publicity and caused such furore that Yusef’s funeral turned into a major event with all city officials, politicians and black leaders turning up on the funeral to offer their condolences and support to Yusef’s mother, Camille. Mayor Jackson promised an in-depth inquiry but did not connect the four murders referring to them as separate acts of violence. Camille and her friends, like many others, were not very convinced with the ‘typical cases of violence’ explanation.

After the highly publicized event of Yusef’s funeral, there was a lull between November 1979 and March 1980 after which the killings resumed at a higher rate with a body or two turning up nearly every month. The lull was broken with a break of pattern, and this time a girl was found dead – Angel Lenair, a twelve-year-old. She disappeared on March 4, 1980, and her body was found on March 10, 1980. She had been tied to a tree with an electrical cord around her neck and a pair of panties (not hers) had been stuffed into her mouth. Medical examination revealed that she had been strangulated to death with the electrical cord found around her neck. Angel’s hymen was found ruptured and there were some bruises in the genital area, too, but those were not considered indicative of sexual abuse by the medical examiner. The interpretation turned controversial later, and whether she was sexually abused or not remains an open question.

On March 11, 1980, just a day after Angel’s body was found, Jefferey Mathis (10) went missing. He had gone to get cigarettes for his mother. Soon enough a blue car was brought to the notice of the authorities when one of Jefferey’s friends, who had last seen him, said that he had seen him getting into a blue car, which could be a Buick. Jefferey’s picture in the newspaper was recognized by one Willie Turner, who reported that he had seen Jefferey in the blue car, but according to him it was a Nova car driven by a white man. However, the information was simply filed away. It is significant to note that the kind of car reported in connection with Jefferey’s disappearance was very similar to the car reported in the case of Aaron Wyche (10) who went missing a few months later on June 23, 1980, and whose body was found a day after under a six-lane highway bridge over the railroad tracks in DeKalb County. Furthermore, soon after Jefferey’s disappearance, a few boys from his school reported to the principal that two black men had tried to lure them into a blue car around the school. The vehicle’s registration number had been noted by the boys and the same had been passed on to the police. But the police did not follow that lead either.

Eric Middlebrooks (14) left his house at around 10:30 PM on May 18, 1980 after he received a call. He had told his mother that he was going to repair his bike. The next morning he was found bludgeoned to death a few blocks away. There was this police theory about his being a witness to a robbery, which led to his murder. But there was no firm evidence to base such theories about.

On June 9, 1980, Christopher Richardson (12) disappeared from Decatur, just outside the boundaries of Atlanta city. He had left for a local recreation center to swim but never reached. Then, in the early hours of June 22, 1980, LaTonya Wilson (7) was abducted from her home, and though a neighbour said that she saw a black man entering the house and leaving with the little child in his arms, there have been serious doubts cast on the accuracy of her statement.

As the disappearance of the children continued with the police investigation getting nowhere around solving the case and apprehending the guilty, public resentment began to rise, and the pressure on the police to crack the case started mounting. The mothers of three of the victims – Camille Bell, Willie Mae Mathis and Venus Taylor – joined Reverend Earl Carroll and formed a group called Committee to Stop Children’s Murders (STOP), which exerted pressure on the Atlanta city government and also pushed the corporate power structure in Atlanta to lend support.

Just a day after Wilson’s abduction, Aaron Wyche (10) disappeared, and was found dead the next day. He had been strangulated to death. The police had dismissed the case as a case of accidental death in the beginning. But the fences on the bridge were as high as Wyche was, and thus there was no way he could accidentally fall off the bridge. Besides, he was unlikely to go up the bridge on his own because he was very scared of heights. On July 6, 1980, Anthony Carter (9) went missing after 1:00 AM, and his stabbed body was found the next day not too far away from his house.

However, the killings were being treated as unrelated cases of homicide. To them it was just an increased rate of child murders in the city. However, the rising political pressure on the authorities led to the formation of a special task force to look into the murders.

However, the killings were being treated as unrelated cases of homicide. To them it was just an increased rate of child murders in the city. However, the rising political pressure on the authorities led to the formation of a special task force to look into the murders.

On July 30, 1980, Earl Terrell (11) went missing from the South Bend Park swimming pool, and her aunt received a phone call with a man sounding like a “white southerner” asking for a ransom of $200 to let Terrell. The man told that Terrell was in Alabama, which meant that he had possibly been taken across the state lines. And the offence of kidnapping and transporting somebody across the state fell within the jurisdiction of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Mayor Maynard Jackson lost no time in getting the FBI on the case as he had been wanting to for quite some time.

But FBI’s involvement in the case could not stop five more killings from taking place between August 1980 and November 1980. All victims were between nine (9) and fourteen (14), and most of them had been strangulated.

The end was nowhere in sight, and the bodies would keep turning up at the same rate until mid 1981.

Originally written for and published in LAWYERS UPDATE as a two-part ‘Crime File’ in December 2012.

Photo Courtesy: Murderpedia