Not the one to break someone’s trust, even if it were that of a lizard with presumably no understanding of such things as trust, (or maybe there are trust instincts, too, who knows? Maybe lizards do, if they know what knowing means. Maybe there are knowing instincts as well), I left it undisturbed, and continued to not use the induction cooktop as before, which was easy to do (or not do?). But when it did not move for a month or so, although hibernation could easily last that long, I began to wonder if it was dead. But dead lizards are quickly consumed by ants, and since there were no ants anywhere close to her, I assumed she was enjoying her hibernatory slumber, which I had no need, reason, or intention to disturb.

When the climate started warming up, I thought it was time for the creature to rise and shine, but she didn’t. So, finally, I gently lifted the cooktop to see how she was doing underneath. She was dead. And yet there were no ants. I figured that since I did not cook very often, there was not much to eat for the ants on my kitchen platform, and so there was no reason for the ants to patrol the kitchen slab, which was also why I often wondered about the lizard’s interest in the area, and could never come up with a plausible explanation.

Dead lizards present no disposal problems. They can be sent down the drains, flushed down the toilet, or be consigned to the dustbin to be disposed of in the regular course with the rest of the garbage. But somehow that never seemed to be the right way to treat this dead lizard that had spent so much time under my electric kettle, and with whom I seemed to have an understanding of sorts. Aren’t all friendships and relationships understandings of one kind or the other? Of course, this was an unequal relationship. The lizard had invited herself to my kitchen platform and had refused to leave, forcing me to accept her terms. True, that save for my initial hesitation, stemming majorly from my reluctance to be the cause of physical harm to her, I did not have much problem agreeing to her terms, but that did not make her terms any less unilateral.

But these thoughts about why it did not seem proper to dispose of those particular reptilian remains the regular way are largely retrospective, and while it is useful to reflect upon why and how we come to attach value to the dead bodies when they are no different than any other insentient objects, back then my thoughts centered more around finding the right way to lay such a creature at rest that had made an effort, deliberate or instinctive, to remain out of my way and had ensured, in her own way, to cause no inconvenience to me, which is more than one can say of so many fully conscious and reasonably intelligent human beings. So I decided to give her a respectful burial.

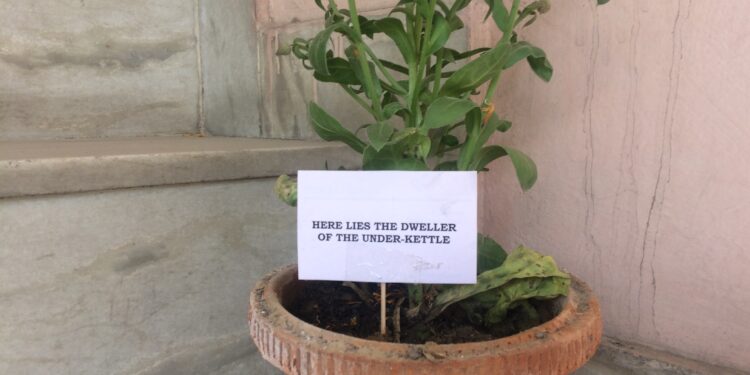

I got three earthen flower pots complete with flowering plants, dug out some of the mud of one of them to make sufficient room for the little body, and lay the dead lizard in the mini ditch thus created before filling it up. I placed the pots on the stairs going to the roof and marked the grave with a small rectangular card on a thin, small stick, held together by transparent tape. On the card, I glued a printed paper, cut to the size of the card, declaring: HERE LIES THE DWELLER OF THE UNDER-KETTLE.

I got three earthen flower pots complete with flowering plants, dug out some of the mud of one of them to make sufficient room for the little body, and lay the dead lizard in the mini ditch thus created before filling it up. I placed the pots on the stairs going to the roof and marked the grave with a small rectangular card on a thin, small stick, held together by transparent tape. On the card, I glued a printed paper, cut to the size of the card, declaring: HERE LIES THE DWELLER OF THE UNDER-KETTLE.

Since, quite obviously, the grave-card could not remain for long, I took a picture of her final resting place for relative permanence. That was on April 6, 2019, the precise date and time of her death being unknown.

Not that it changed much. I still don’t like lizards, but hey, I don’t like human beings in general either.

Concluded

Originally published as part of my monthly column Street Lawyer in the March 2021 Issue of Lawyers Update (Vol XXVII, Part 3).