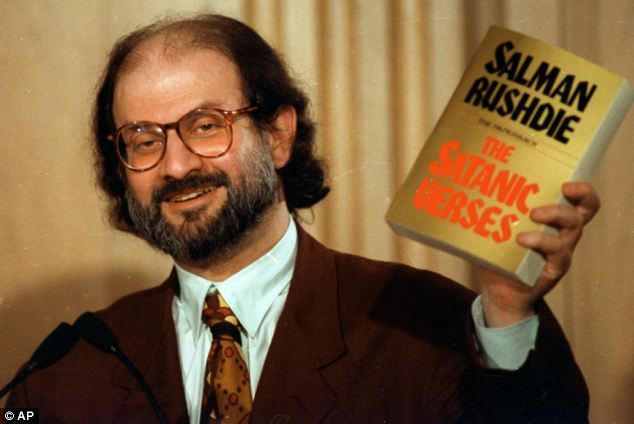

On October 5, 1988 we banned a book called ‘The Satanic Verses‘ without reading it just nine days after it was published in the United Kingdom. Nine days? Shouldn’t it take much longer to import, ‘decipher’ the ‘unreadable’, and make a decision? It wasn’t published in India and was yet to be formally marketed in this country. So, what did we ban? It’s import under Section 11 of the Customs Act, 1962.

Cut to the Jaipur Literature Festival, 2012. We disallowed the author of the book – Sir Salman Rushdie – from participating in the event, not even through video conferencing.

What’s ‘banned’, again? The book or the author? The ban under the Customs Act bars the book from entering the country, alright. Does it also bar people? Under the Customs Act, 1962, are people ‘importable commodities’ that can be ‘barred’?

What’s ‘banned’, again? The book or the author? The ban under the Customs Act bars the book from entering the country, alright. Does it also bar people? Under the Customs Act, 1962, are people ‘importable commodities’ that can be ‘barred’?

Yes, I know the standard ‘public order’ argument. Can a person be prohibited from speaking in public just because what he ‘might’ speak ‘might’ be ‘hurtful’ to a section of people? If a person is so stopped, is it not – technically speaking – pre-censorship? Therefore, is it not the violation of the Right to Freedom of Speech and Expression guaranteed by Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution?

There is no reason for us to believe that Mr. Rushdie was about to deliver an inflammatory speech because he has not said anything even remotely offensive on any of the earlier occasions when he was in India or when he participated in the Jaipur Literature Festival, 2007. And nothing has really changed on that front.

It might also be noted that the Jaipur Literature Festival came to the attention of the world because of Rushdie’s participation in the first place. Furthermore, Rushdie is a writer of international repute and not a politician. As a writer what he needs is ‘readers’ and not ‘voters’ or ‘supporters’. So, making inflammatory speeches doesn’t really work for him irrespective of its efficacy for the politicians.

Besides, Rushdie has already had truckloads of such negative attention, which got him fatwas and attempts on his life. With the nightmare still fresh in his memory, he is very unlikely to invite more trouble by infuriating people at the Jaipur Festival for no good reason. In all likelihood, he wanted to ‘participate’, and in denying entry to him we certainly refused to defend his right to speak and our right to hear him, and also ended up offending the Constitution in the process in more ways than one.

Now, assuming that Rushdie’s presence could cause some unrest; may be more than ‘some’. But then, is the possibility of a law and order problem alone a valid ground to restrict or deny right to freedom of speech and expression? The answer quite obviously is ‘no’ because if such a ground was allowed, it would be the end of all peaceful, democratic protests, and, by extension, the end of democracy as well. Therefore, in absence of any valid reason, the decision to bar Rushdie – whichever way it was done – from participating in the Jaipur Festival was clearly “unreasonable and arbitrary” and thus offended Article 14 as well.

And this has nothing to do with Rushdie’s literary merit as an author or the social utility of his work. He might be ‘substandard’, ‘unreadable’ or ‘overrated’, but that does not diminish his right to be treated fairly.

If ‘utility’ of any kind is the parameter, let’s start by burning Monalisa because her inscrutable smile surely doesn’t alleviate poverty or crime or AIDS, and then we can move on to Khajuraho with a sledgehammer because at 123 million and counting, we surely don’t need temples with erotic statues to tell us how to do ‘it’.

And if ‘quality’ is a criterion, all but the today’s Shakespeares, Joyces, Kalidases, Kants, Picassos, Miltons, Premchands and the like must be decreed to stop work at once. Those who can’t speak as well as Martin Luther King, Jr. must be told to shut up. And the farmers would stop committing suicide, hopefully.

If being ‘inoffensive’ is a necessary precondition, Mirza Ghalib was offensive enough to border on blasphemy. And in his day and time, he was considered ‘substandard’ by his contemporary poets like Mohammad Ibrahim Zauq. Publishers did not find him ‘publishable’ for a long time. And his poetry did not stir up a revolution then, nor can it do so now. So, he was a socially ‘ineffective’, ‘substandard’, ‘almost blasphemous’ poet. Imagine the literary consequences of silencing Ghalib for those reasons, shall we?

Originally written for and published as Opinion in LAWYERS UPDATE [March 2012 Issue; Vol. XVIII, Part 5]